Would it be more illuminating in understanding the Harley lyrics to shift the terms of thematic analysis from vernacular spirituality to indigenous spirituality?

The term vernacular spirituality came to my attention through a special issue of the Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies (which I’ve misplaced, and the JMEMS online presence only goes as far back as 2000). The term distinguishes Catholic spiritual texts written in the official language of the Church, monasteries, and universities from those written in English, French, Spanish, German, and other mother tongues. The assumption is that they are written for largely lay audiences and do not reflect applications among clerical or regular communities. (See McGinn, 2012; Watson, 2022.)

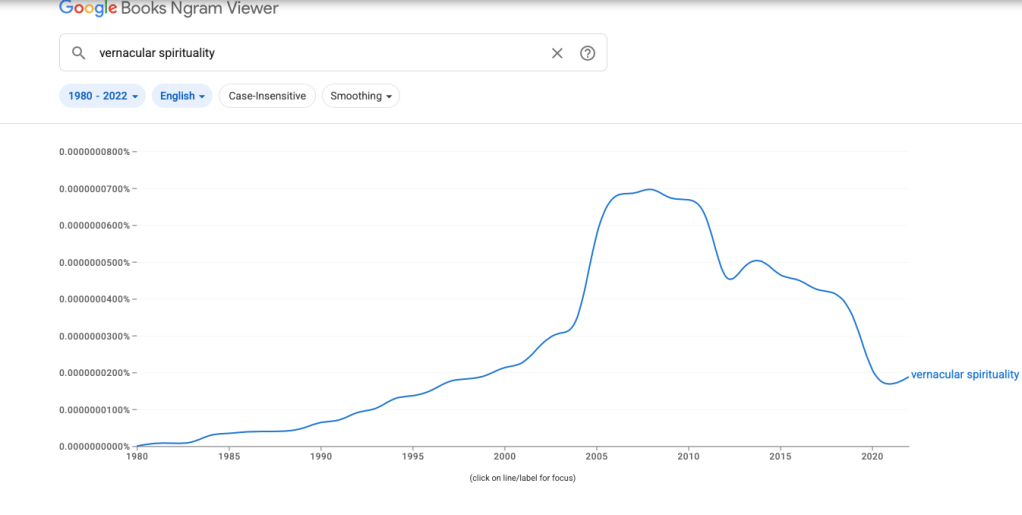

The term appears to have proliferated between 2003 to 2010 (if Ngram is an accurate guide).

However, the case for late medieval England is rather more complicated. There are at least two mother tongues: the French of England and Middle English (but also Welsh, and Cornish, and Gaelic, and Scots, although these don’t appear in Harley 2253). Anglo-Norman French was the high status language, and it must be said the colonizer’s language, while Middle English (much changed since its Old English stage) might be characterized as the indigenous or subaltern language of England in the early fourteenth century.

So how might we look for a distinctly indigenous spirituality in Harley 2253’s vernacular Middle English? What I propose is a closer examination of poems with one or both of two features: 1) persistent use of alliteration (though not in the strictest sense “alliterative verse” [see Weiskott, 2016]) and 2) macaronic verse (employing two or more languages in alternating lines) when Middle English is employed.

Alliteration (the Old English form of “rhyming” among Anglo-Saxon texts by the repetition of initial consonants in a line) appears to have gone underground after the Norman Conquest, reemerging in the fourteenth century in the so-called Alliterative Revival. Many of those works, like Harley 2253, are associated with England’s West Midlands: the four poems of the Pearl Poet (Pearl, Cleanness, Patience, and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight) and William Langland’s Piers Plowman (Langland was born in the West Midlands around the time that Harley 2253’s scribe was compiling his MS).

Macaronic verse flourished in the High Middle Ages, apparently in scholarly circles where Latin was the professional language alongside everyday vernaculars. Most famous for macaronic verses is the compilation known as the Carmina Burana (set to music in the twentieth century by Carl Off) in which Latin engages in conversation with French and German.

My task will be to discern distinctive thematic characteristics in the lyrics employing stylistic alliteration and to look for distinct voices in the macaronic dialogues of competing Latin and Middle English.

Leave a comment